Over the past four years, I’ve been on a mission. I’m tired of seeing people, myself included, cave under pressure and perform at less than our best. To solve this problem, I’ve worked closely with former Major League Baseball pitching coach and mental game guru Rick Peterson as well as a number of other elite coaches and performers in business, sports, entertainment, and the military. What does Rick know about performing under pressure? He is renowned for getting Hall of Famers, All-Stars, as well as average pitchers to calm down in the highest stakes situations, in thirty seconds or less, and come through in the clutch.

Rick’s and my experience and interviews with elite performers reveal that, even more than physical skills, it’s performers’ mindsets that separate the best from the rest under pressure. Clutch performers start by recognizing their instinctive thoughts don’t serve them under pressure. They know how to flip the switch, to think on command in counterintuitive ways that help their performance.

Here are four counterintuitive tips you can use to be your best in your high-stakes situations. I didn’t know these tips until I interviewed Rick, Navy SEAL Ed Hiner, and Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Glavine.

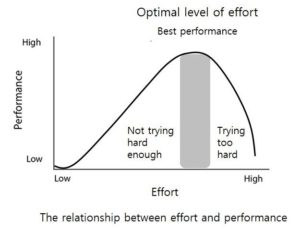

- Don’t try harder; Try Easy! Contrary to what many of us were taught, trying harder under pressure is often counterproductive. Many examples, across a number of fields—athletic, military, and business—show that trying harder leads to a decline in performance. Think about your best performances. Were you grinding and full of anxiety? More than likely, you remember your best performances as almost effortless.

Try Easy is not about not trying or being lazy. It is about throttling back just a little. It’s about taking the tension out of what you’re doing and replacing it with a level of effort that allows you to perform in a relaxed state. Optimal performance does not come from maximum effort; it comes from optimal effort.

Figure 1: The relationship between effort and performance

- Under pressure, humor isn’t a nice to have; it’s a must have. Humor diffuses pressure better than any pharmaceutical on the market. It momentarily reduces the perceived threat posed by the situation. It also helps generate a sense of control and provides perspective that can help you see dire situations with some levity. It also stops the stress hormome, cortisol, in its tracks and releases endorphins, the feel good neurotransmitter that enhances performance.

Rick regularly used humor on his visits to the mound to calm his pitcher down and get him back on track. Consider the following exchange between Rick and relief pitcher Jason “Izzy” Isringhausen, on the mound of Yankee Stadium in front of 57,000 screaming fans, American League playoffs, 2-0 lead, runners on first and second base, nobody out, bottom of the ninth inning.

Rick: Hey Izzy, how’s it going?

Izzy: I can’t feel my legs.

Rick: That’s okay, we don’t need you to kick a field goal. (Izzy laughs). Remember, you’re a professional glove hitter. You’ve done it thousands of times before and you’re going to do it again here.

Izzy proceeded to get the next three batters out and save the game. Crisis averted.

- Shift your source of confidence like a SEAL. Most people base their confidence about an upcoming performance on their most recent performance. When they perform well, they’re confident. When they don’t perform well, they aren’t. The obvious drawback of this approach is that performance fluctuates, in some cases based on conditions outside your control.

Consider the great confidence a young Navy SEAL takes with him into battle, even if he has no combat experience. The SEAL’s confidence is based upon his intense preparation and skill acquisition, not upon his prior performance in battle.

“We call war ‘monkey business’ because of how easy it is compared to training.”

—Brian “Iron Ed” Hiner, retired Navy SEAL

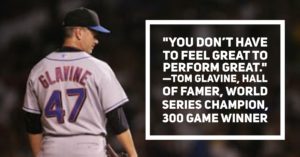

- You don’t have to feel great to perform great. Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Glavine shared a surprise with me during our interview. He said he only felt great—was in the zone—one out of every five starts he made. The other four times, he said something was missing. Glavine said, “My career really took off when I learned to how to win games when I didn’t have my ‘A’ stuff (best pitches working for me). I learned how to win that B+ game or that C+ game (where I was pitching less than my best). That really made all the difference because now I have confidence to win when I’m not at my best.”

If the Hall of Famer Glavine was in the zone only 20 percent of the time, then how realistic is it that we will find ourselves in the zone more often? When you aren’t feeling it, dig in and learn to win with what you do have in that moment.

Different and better thinking is the starting point to experiencing the pure joy of coming through in the clutch.

ast night at the YMCA. Hope you had a great workout.

ast night at the YMCA. Hope you had a great workout.